What's

Filter bubbles distort reality. How to avoid them?

Bubbles can certainly bring benefits. During the quarantine, we were advised to stay in bubbles to avoid contracting COVID-19. In the online space, bubbles can prevent us from being overloaded with information. But so-called filter bubbles like these can also have a severe negative effect on people. We recently began to study this effect with our team. Why is it important to research filter bubbles? Why is bursting your bubble worthwhile? And how can you do it?

When are we closed in a bubble?

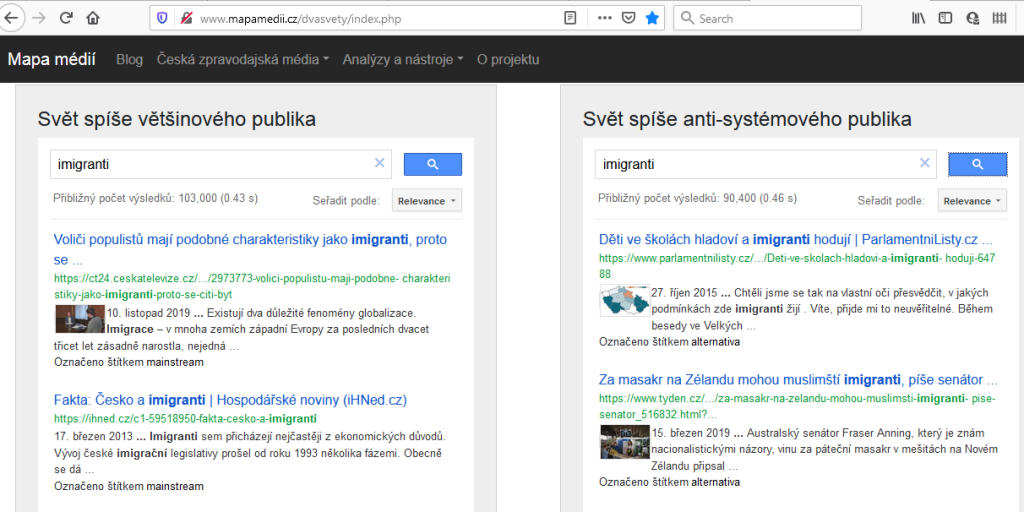

A filter bubble is a state of intellectual isolation resulting from the personalization of internet devices and is most common on social media and search engines. Because these tools modify their output based on our behaviour, we ourselves must take responsibility for our bubbles, rather than passing the blame onto the algorithms. It is often difficult to hear an opinion that diverges so far from our own, and some topics simply don’t interest us. Sometimes an emotionally charged post grabs our attention. In such instances, the algorithms listen to us too closely and accommodate our wishes all too readily.

This constant conformance to our preferences is not always to our benefit, particularly in politics. Intense arguments between conservatives and liberals arise because each group only follows their own media sources and loses perspective on the opposing point of view. The less information we have from “the other side,” the more we disconnect and cease understanding one another. As a result, society becomes polarized, making it more vulnerable.

Dangerous consequences of bubbles

The polarization of society into two or more fractions has resulted in some of the worst events and acts that people are capable of—civil wars and genocides. In an atmosphere of division, disagreements between people lead to a loss of understanding for the other side. Adding propaganda, dehumanization and disinformation to the mix breeds outright hatred, even towards your own neighbors and friends, as happened in Rwanda and Bosnia.

How do social media influence these events? After all, many users rely on social media as their main or only source of information. The most salient recent example in which social media were associated with genocide occurred in Myanmar with the massacre of the Rohingya. For many in that country, Facebook was the only source of information and it acted as a hotbed of hatred, dehumanization and incitement to violence. Many other ethnic and religious groups are currently endangered for similar reasons. Muslims suffer attacks in India and Sri Lanka after rumors and hateful statements have been shared through WhatsApp. In Slovakia, hostility has been stirred against Roma, artists, intellectuals, and other minority groups. We can have very little influence over such attacks, but we can make sure that we ourselves do not fall into a polarizing bubble that divides society.

How can we escape our bubbles?

One simple piece of advice that is very hard to fulfill is to actively expand your horizons. This means stepping out of your comfort zone and opening your mind to other points of view and other topics, which can be especially challenging in matters of values in which we already have deep-seated opinions—abortion, immigration, climate change etc. But listening to others doesn’t mean we’ll change our opinion. It’s usually enough to understand and accept the valid arguments of the other side. In an offline environment, this is much easier than online, where we don’t see opponents or their human qualities, which are so important to empathetic communication.

Personalization of services sometimes ensures that we don’t even know about our bubble. We are simply fed information that we agree with. In such instances, we need to try more actively to escape our bubble. It is helpful to spend time setting up your internet privacy to ensure that content is tailored as little as possible. For example you could:

- use search engines that do not tailor results based on your data, such as DuckDuckGo

- use plug-ins for browsing social networks without personalization or politics, such as Social Fixer for Facebook

- better set up your privacy and cookie settings in web applications.

With all that said, we believe that users should not only be left to defend themselves in cyberspace—not everyone is able, so we welcome the activities of the European Commission in this area, who have introduced legislative steps like GDPR, educational activities such as European Media Literacy Events, support for research in this area and publications like the recent Technology and Democracy report.

We need more research on filter bubbles

Independent research will help us to better understand, how algorithms and we ourselves influence the formation of filter bubbles. One important question is, how should internet tools be modified to connect rather than divide people. We are preparing an audit of filter bubbles, which could show us how quickly a YouTube user can fall into such a bubble and how quickly they can come out. Does a simple change in users’ behavior have any effect? Or do you need to erase your entire history and unfollow certain channels? We will inform you of the results of this research in future blog posts, so we recommend that you follow our blog.

Basic literature on this topic

BAKSHY, Eytan, Solomon MESSING a Lada ADAMIC, 2015. Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. In: Science. Washington: American Association for the Advancement of Science, 348(6239), s. 1130-1132. ISSN 1095-9203. Dostupné na: https://goo.gl/btjwGv

BESSI, Alessandro, 2016. Personality traits and echo chambers on Facebook. In: Computers in Human Behavior. Amsterdam: Elsevier, s. 319-324. ISSN 0747-5632. Dostupné na: https://goo.gl/nKcwCW

PARISER, Eli, 2011. The filter bubble: what the internet is hiding from you. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-92038-9

SUNSTEIN, Cass, 1999. The Law of Group Polarization. Chicago: University of Chicago Law School. Dostupné na: https://goo.gl/z1gr5E

VICARIO, Michela et al., 2016. The spreading of misinformation online. In: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Washington: National Academy of Sciences, 113(3), s. 554-559 . ISSN 1091-6490. Dostupné na: https://goo.gl/UibJe2